INTERRUPTED JOURNEY

The CAPE VERDE 1828 SHIPWRECK of the ‘LETITIA‘ OUT OF IRELAND CARRYING EDWARD CONYNGHAM and OTHERS.

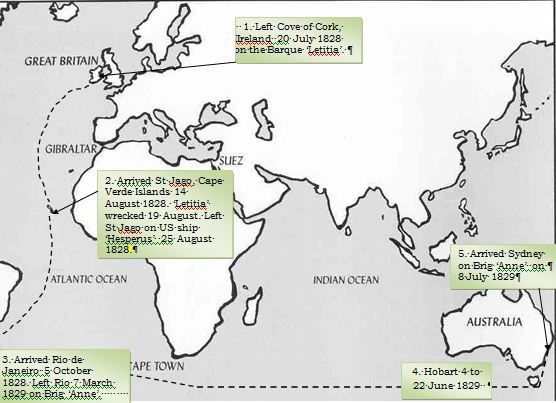

Cove of Cork July 1828 to Cape Verde August 1828………….. “Letitia”,

Cape Verde August 1828 to Rio de Janiero October 1828……………. “Hesperus”,

Rio de Janeiro March 1829 to Hobart and Sydney January 1829………………..”Anne”

[NOTE: Some of my research notes are attached. See the list at the end of this page.]

My great great grandfather, the 22 year old prospective emigrant Edward Conyngham joined a fifty strong group of families, including eleven women and nineteen children, on the dock at Cove in July 1828. (Major) Humphrey Grey from Roscomroe in King’s County; (Commander) William Moriarty from Summer Hill in Cork, John Gee of Rathmolyn, Co. Meath, Henry Gee, his cousin, all with their families and some with servants, following, like Edward Conyngham of Dublin, siblings already settled on the other side of the world. The irascible Joseph Henry Moore, son of the Earl of Drogheda, and his family, from Dublin; Richard Popham of Bandon, Co. Cork; Dr Jonathan Clerke, his brother Alexander, with his wife, married only days before in Skibbereen, Co. Cork on 19 June, gathered their belongings. Mrs Ann Weston, together with her son, joined the group, setting out to join her husband, Superintendant of the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney. And a number of single men of various ages taking their chances in the new Colony. They, as well as the aforementioned men, aware of and drawn by the certainty of land grants, planned agricultural pursuits, shipping the necessary farming implements with their family possessions and furnishings. The Greys even brought a cow, though that was to provide fresh milk for the children en route.

H V Morton visited Cove in 1930: “A few miles from Cork is the saddest spot in Ireland – the port of Queenstown, known now as Cobh, which is pronounced as Cove. This place has heard, and will hear again, the keening of mothers lamenting as if for the dead. …over three-quarters of a million young Irish men and women have gone away from this port. Queenstown is a wound which Ireland cannot staunch; and from it pours a constant stream of her best and youngest blood.” [1]

A century earlier, Mr and Mrs S C Hall visited the same spot:

‘We stood in the month of June on the quay at Cork to see some emigrants embark in one of the steamers for Falmouth, on the way to Australia. The band of exiles amounted to two hundred, and an immense crowd had gathered to bid them a long and last adieu. The scene was touching to a degree; it was impossible to witness it without heart-pain and tears. Mothers hung upon the necks of their athletic sons; young girls clung to elder sisters; fathers – old white-headed men – fell on their knees, with arms uplifted to heaven, imploring the protecting care of the Almighty on their departing children. ….Amid the din, the noise, the turmoil, the people pressing and rolling in vast masses towards the place of embarkation like the waves of the troubled sea, there were many such sad episodes. Men, old men too, embracing each other and crying like children. Several passed bearing most carefully little relics of their homes – the branch of a favourite hawthorn tree, whose sweet blossoms and green leaves were already withered, or a bunch of meadowsweet. It is impossible to describe the final parting. Shrieks and prayers, blessings and lamentations mingled in one great cry from those on the quay, and those onshipboard, until a band stationed on the forecastle struck up “St Patrick’sDay”. ‘Bate the brains out of the big drum, or ye’ll not stifle the women’scries,’ said one of the sailors to the drummer.” [2]

The ‘LETITIA’ left Cove on 19 July 1828. She could have expected to be in Port Jackson in the following December at the latest.

Some of the passengers were unhappy with Clements. The crew he took on appeared to be incompetent and the food and water were below standard. Humphrey Grey, bound with his family to Van Dieman’s Land, wrote to his cousin in Ireland in the following terms:

“I must give you an account of our proceedings since we left Cork Harbour. We were sent to sea with the worst crew that were ever shipped on board any vessel. They could hardly work her out of Cove. Repeatedly, the Pilot said the crew knew nothing about the management of the ship. Mr Harris, the Customs House Officer, where he was taking leave of Captain Moriarty’s child, said, “My dear, I hope you may arrive in New South Wales, but I foresee it will not be in the Letitia!”

We had only five hands on board that knew any thing about seamanship, and three of them were as great villains as could be met with. They were picked up in Cove as the crew that shipped on board in Dublin left her in Cove. Repeatedly, these fellows said the ship would be lost for want of hands to work her. Clements said he would put into Madeira and ship three or four hands. Instead of doing so, he went into the harbour, and on finding the Port charges would be about £6, he stood out to sea, leaving us at the mercy of the waves, with a promise to put into Pernambuco (Brazil) for fresh water and provisions. Our water was bad four days after we left Cork as the casks that contained it were dirty and bad.

Almost every day there was a row between the Captain, passengers and crew. We were blessed with a fair wind fdrom two days after we sailed, until we anchored in Porto Prayo.”[3]

The ship arrived at St Jago in the Cape Verde Islands, a regular stopping point off the West Africa coast, for water and fresh food on 14 August, 1828 and was wrecked on the rocks in bad weather on 19 August.

The British Consul, John Goodwin, wrote shortly after the ‘Letitia’ incident:

“Porto Praya.

This is the chief town of St Jago and the Capital of the Verdes. It is situated on the southern side of the Island and contains about two hundred and fifty houses and a thousand inhabitants. It stands upon a tableland about 150 feet above the level of the sea, under a chain of barren mountains. It is the Residence of the Governor General and likewise is the chief seat of commerce in the Cape Verde Islands. Its regular trade is chiefly in the hands of the Americans but many English Vessels bound for the Indian and South Pacific Oceans touch here to take water and provisions. Water is put on board at a dollar a pipe, and livestock of all kinds, vegetables, fruit and tropical productions in general are furnished at reasonable prices. The harbour of Villa da Praia is considered to be safe from the 1st November till the middle of July when the rollers set in from the southward, and make the anchorage insecure. St Jago is always unhealthy but it is particularly so during August, September and October in which months the rain comes down in torrents, forming large pools of water, the exhalations from which produce fever and sickness.” [4]

Humphrey Grey prefaced his letter with an account of the incident:

“I suppose you will hear ere this reaches you of our shipwreck. We are thank God all safe with an entire loss of property excvept for a few torn rags that we got on the shore next day. On the 15th of August, we came to anchor at Porto Prayo Island, off St. Jago, to take in water as what we had on board was very bad. It came on to blow, which occasioned a swell and the ship rolled much. It was deemed advisable to let go the second anchor, which was neglected by the Captain.

We were then in 8 fathoms of water with less than 30 fathoms of chain out, and about 3 o’clock on the evening of the 19th she parted her anchor by the chain breaking. Then, too late, the second anchor was let go, but did not hold. You may judge what a situation we were in, leaving the boat and getting most of the passengers ashore. A signal was made, which brought a boat alongside. We instantly got all the Ladies and Children in her and sent them ashore. Shortly after 4 o’clock, she struck on the rocks, with a dreadful surf.

She soon began to fill, and the masts to roll, which made it dangerous to stay near her. I remained on board till her lower deck was forced up to the upper one. I am sorry to say that no exertion was made to save the ship or cargo. The wind abated before the chain broke. I wanted Clements to let the kedge anchor be run from the ship, but he would take no notice of what any person said. We can never give sufficient thanks to the Almighty, for, had it happened at night, I think (five? we?) would not be saved.

Owing to the great heat of the weather, the Ladies had on only a gown, and the gentlemen a jacket and trousers, and in that state, we are now obliged to remain, for want of others to change them. I have seen some shipwrecks, but anything to equal this, I have never witnessed. She was actually torn to pieces!

We have experienced much kindness from Mr Goodwin, the British Consul, who provided us with provisions and lodgings during our stay and a passage for as many as wished to go to Rio de Janeiro.”

July was undoubtedly an unsuitable time for ships to be calling at St Jago. These unhealthy fevers and diseases were well known to mariners to be prevalent at the time. The harbour was known to be insecure from August to October, when storms rolled in from the Atlantic. Captain Cook’s Log of his third journey, when, after almost coming to grief against Boa Vista, a little north of St Jago in the same group of islands, he called in for fresh water and provisions at St Jago in precisely the same week, though fifty six years earlier, reported the gales right through the week he was in the vicinity. [5] Moreover, two of his sailors died and others fell ill from fevers caught in St Jago. [6]. Furthermore, the 11 ship First Fleet, sailing to New South Wales tried to enter St Jago harbour in June 1787, but found the winds and swells dangerous and continued on to Rio.

British Consul Goodwin, although he had taken up his appointment only a few weeks earlier, was well aware of the health problems. He wrote later to the authorities in England:

“ It is not once in three years that a homeward bound English Vessel touches at this Port, and to send the distressed people to Sierra Leone to get a passage to England was found to be a hopeless endeavour. The fever had already broken out, when the Hesperus, Captain Allen, came in and I determined, on mature consideration to send the people to Rio de Janeiro, whence they might prosecute their voyage to New South Wales, or procure a passage to England.” [7]

The first that relatives or officials back in Ireland would have known of the wreck was this short item in Lloyd’s List on 18 November, information probably obtained from the ‘Mary’ by passing UK bound ships and reported without detail to Lloyds. The facts behind the wreck were not available until a month later when the Dublin and London newspapers reported:

Wreck of the Letitia, Capt. Clements.

“ We have been favoured with the perusal of a letter from Porto Prago, Island of St Jago and another dated 22nd of October last, from Rio de Janiero, stating some of the particulars of the unfortunate loss of the above vessel, and the fate of the passengers; and as many of them have friends in this city, we publish the following particulars:- On the 14th August last, the Letitia anchored in the Bay of Porto Prago, to take in water and some fresh provisions, and on the 19th, although the weather is represented as being moderate, it appears she drifted on the rocks, and shortly after bilged and became a wreck. The passengers and crew were all landed safely, being near the shore…but little or nothing was saved of the cargo or the passengers’ luggage.” [8]

There were no fatalities, though all property was lost. Three passengers –Mrs Weston, and child, destined for Sydney as well as John Murphy for Hobart – were taken on board the “Mary” the same day and carried on to Hobart and Sydney.

Later the British Minister in Rio, claiming to know of “…the baleful nature of the bad season at St Jago…” wrote that “… the Consul’s prompt dispatch of the group “probably saved a large part of their number.” [9] Moreover, accommodation was apparently a problem on the island. The Consul, reporting to the Foreign Office stated that his Vice Consul Gardner,

“…..on the melancholy occasion of the loss of the’Letitia’, in August 1827 (sic), received into his house 64 of the passengers and crew, and shewed them every attention and civility in his power.”

Forty one survivors, together with six crew, were sent within days under charter arrangements made by the British Consul – concerned at the effects of prevalent diseases and fevers – to Rio de Janeiro on the American Ship “Hesperus”.

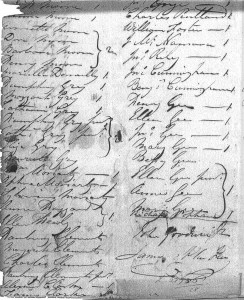

The Contract [10] dated 23 August 1828 provides some context of the conditions Edward and others endured on the ‘Hesperus’ en route to Rio:

Contract – Consul Goodwin and Capt Jas Allan of the “HESPERUS”. It is this day agreed upon between John Goodwin Esq., His Britannic Majesty’s Consul for St Jago on the one part , and James Allen Jnr., Master and Owner of the American Ship Hesperus on the other part, that for the consideration hereinafter mentioned, that the said Jas Allen doth engaged to convey in his ship Hesperus to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil the passengers or such part thereof as shall agree to embark, of the British Bark “Letitia”, Hanbury Clements, Master, wrecked on the 19th Inst in the Bay of this Port on her voyage out to New South Wales, agreeing on his part to give the free use and reach of his ‘tween decks for the accommodation of said passengers, together with firewood and use of cambouse (stove) only. The said Consul on his part agreeing to put on board all the necessary provisions and water for the supply of said passengers. And it is agreed that the said James Allen shall receive the sum of 45 Dollars each for such numbers of passengers as shall embark, the number when ascertained be inserted on the back of this Agreement and duly certified and signed by us. The freight on passage money payable by Mr Goodwin’s draft on the British Treasury at the rate of 4/6 per dollar at the date of embarkation. It is further agreed that that the said passengers shall embark on the Hesperus on the 25th August, 1828.

Signed at Villa de Praya, St Jago,23rd August, 1828 John Goodwin, Jnr, HBM Consul and James Allan Junr.

Humphrey Grey continues:

“We left four of our passengers on the Island of St. Jago, who intend returning to Ireland by America, viz, Mr. Page, son to Mr Page, stockbroker Dublin; Mr. Hill, Dublin; Mr. Roberts, near Derry; and Dr. Clerke, of Skibbereen. Mrs. Weston and child of Cork went on in the Mary of London next day. She did not save a stitch of clothing nor a shilling of money Mr. Murphy, of Dublin, also went in the Mary.”

Two of the four – – who remained at St Jago made it back to Ireland, one being Dr Jonathan Clerke, who reached Hobart a year later. Two – Hill and Roberts – did in fact perish on the island in a very short time.

Continuing Humphrey Grey’s letter:

“We have on board the “HESPERUS” of New York, Captain Allen, Master bound to Rio, Mr. Moore of Dublin wife four children and servants; Mr. Pentland (the Super-Cargo); Mr Onga, Dublin; Captain Moriarty, wife, child and two friends of his; steerage passengers; Captain Clement’s wife and two children; Mr. L.W. Clerke, Skibbeeren; Mr. Popham from near Bandon; also part of our former crew.”

Perhaps the party was not aware that the next sector could be dangerous for a different reason. Two American brigs had had been boarded and one robbed of considerable property by pirates a month earlier in the vicinity. The Pirate Captain had stated that his intention was to rob every American and English vessel. In another incident the US Consul in Rio reported that pirates robbed an English ship, treating the captain with great brutality. [11]

The Dublin newspaper report continued:

On the 27 August, 46 passengers, including the Captain and his family, proceeded in an American vessel to Rio de Janiero, where they arrived in 39 days, having lost seven of their number viz, Mr McGee (sic) and his wife, Mr Hamilton, Mr Lowry, Mr Cunningham Jr, Mr Lindsay and Mr Clerke’s servant; the five latter were all young men and their deaths are stated to be mainly attributed to bathing in a tropical climate. We are happy to state that Mr Charles Pentland, although attacked by fever and ague, was recovering, and that Mrs Moriarty, who was confined on board with her child (a boy) was doing well. It will be gratifying to the friends of Mr Moore, of this city, who with his family were on board the Letitia, to learn that they arrived safely in Rio, where they again proposed to take shipping to their ultimate destination. Another letter has been since received from the British Consul at St Jago, which states that Mr Edward Roberts, one of the passengers who preferred remaining on that Island, waiting for a passage home, died of fever on the 6th October last.”

The ’HESPERUS’ arrived in Rio on 5 October 1828, though, as the newspaper report above states, seven had died en route. Henry Gee and his wife left a very young child, brought on to Hobart by his cousin and his family. It is likely that Hamilton, Lindsay and Lowry were ‘Letitia’ crew. The reference to the death of “Mr Cunningham Jr” is interesting. It is likely that he was William, born 1811, younger brother of Edward Conyngham. On the passenger list written on the reverse of the Consul’s contract with the Captain of the ‘Hesperus’ [12], the two Cunningham names are listed together, as were all other family members. However one name is written as ‘John’ and the other illegible as “B….”, perhaps Benjamin, or Bill. Such is the inaccuracy and ambiguity of written records of the time. The signatures transcription of the petition to the British Consul in Rio has “Edward”.

Immediately on arrival in Rio the survivors, over the signatures of the adult male passengers, including ‘Edward Cunningham’ (sic), petitioned the British Consul [13] to arrange to cover the cost of their accommodation and to send them on to their intended destination:

“We, the undersigned passengers in the late Bark “Letitia” from Dublin and Cork for New South Wales beg to acquaint you that having been wrecked in the Bay of Porto Praya, St Jago, have arrived here in the American Ship “Hesperus”, in which ship they have been forwarded by the British Consul at the Cape de Verds.

On presenting you with the despatch which he has forwarded, he has doubtless represented the total loss of property we have sustained – and the consequently deplorable circumstances we have been reduced to, we have therefore to solicit that you will afford us such assistance as will enable us to prosecute our voyage and that you will also be pleased to subsist us while remaining here.

We have the honour to be etc etc

Wm Moriarty and family

H Grey and family

Alexr Clerke and family

Richd Popham

Wm Forster

Jos Henry Moore and family

Chas Pentland

John Onga

John McNamara

Steerage

John Ghee and family

John Reilly

Edwd Cunningham.

One of the passengers, Joseph Henry Moore, who was travelling with his wife and family, wrote also from Rio to Lord Francis Gower at the Colonial Office, blaming,

“the misconduct of the Captain and crew ”causing the ship became a complete wreck in a few hours, …leaving me and my family destitute of everything save the clothes we had on us.” [14]

Another, Clerke, submitting a claim for land in VDL in 1834, wrote:

“On the 20th of the following month we were wrecked, and thrown destitute on St. Jago, one of the Cape De Verde Isles; being by this event deprived of almost every thing we had on Board and after experiencing sickness, with many other privations unnecessary to mention, the British consul forwarded us by an American Ship to Rio De Janeiro, in this situation I found myself under the necessity of returning to Ireland to procure another outfit, and with these views, I sent on my family to this Colony with the intention of following as soon as I could arrange my affairs…………..”

And John Robert Murphy in a Memorial to Lt Governor Arthur in 1829, stated that he:

” was a passenger in the Letitia of Dublin, which was wrecked at St Jago (19th Aug 1829) (he’s mixed his years up here) that memorialist had property on board for which he paid £900, he also had paid £80 for his passage. The Letitia proved a total wreck, by which memorialist lost all, with the exception of one trunk, with which he sailed from St Jago next day on board the Mary, under the impression that if he remained, he might fall a victim to fever, from overexerting himself to save his property….”

Hanbury Clements and his family, perhaps unpopular with the survivors, moved on quickly, taking passage on the “Jupiter” from Rio to Sydney where he was granted land in the Bathurst area. (His two year old son, Hanbury Jr, who learnt to walk while on the ‘Letitia’, was instrumental, thirty years later, in rushing to inform Police of the infamous Eugowra Gold Escort Robbery by Ben Hall, Frank Gardiner and others.) Five others left Rio, travelling to America en route back to Ireland, from where three – Alexander Clerke, (whose wife carried on to Hobart), John Onge, who was granted land in northern NSW, and Richard Popham, granted land at Bungonia, as well at on Ginninderra Creek, now inthe suburb of Latham, in Belconnen ACT. – would set out again the following year.

Thus 31 of the 39 who arrived in Rio in October awaited the efforts of the British Consul. These were put up in the Hotel de L’Empire, the UK Government meeting their living expenses. Normally, the consular responsibility to a group such as this is to return them to the United Kingdom. However in a series of minutes between the Consul and the British Minister in Rio, there was debated the option of sending them on to New South Wales. After comparing relative costs, and taking the petitioners’ preference into account, they decided, and without time to consult the Foreign Office, to fund their onward journey to New South Wales. [15]

The Consul proceeded then to charter a ship for the purpose, costs being extremely high due to competition from charterers in the River Plate, and made more difficult by the unwillingness of ships’ owners to depart from the current lucrative trade of loading freight for England in order to transport passengers. On 13 December 1828 he accepted a £900 tender from the ship’s agents who actually purchased the “Anne’ for the purpose. The ‘Anne’ had been launched in Prince Edward Island in June 1825, and sent., as was often the custom, to be prepared in Liverpool, where she was fitted and coppered, and may be said to have commenced her career as a Merchant Vessel, with a cargo for Buenos Aires in February 1826. In May of the same year, she was arrested by the Brazilian Squadron blockading Buenos Aires, and brought to Rio where she was under trial for about a year, and was released. It had completed some journeys carrying freight.

Consul Heatherly hoped that the Anne, when fitted out, would be ready for sea in a few days, as he advised the Superintendent of the Consular Service at the Foreign Office.[16] He had arranged with the Captain of the British HMS ‘Ganges’ to allow the carpenters and some seamen to assist in laying decks and fitting the vessel for departure by 1 January. Unfortunately, the ‘Ganges’ had to put to sea in late December and local carpenters and caulkers were unavailable as the Brazilian government was requiring all available trades to fit out their own vessels of war. By mid January the ship was not ready, leading Joseph Henry Moore to write to the Consul, claiming that the ‘Anne’ was not seaworthy, and asking that the passengers to be sent on to New South Wales on the “Denmark Hill’ then in port. The Consul disputed Moore’s claim, though he assured him that the ‘Anne’ would be surveyed and declared seaworthy prior to her departure. As for the option of using the ‘Denmark Hill’, he ruled this out, since a contract had already been signed with the agents of the “Anne’. There followed a series of exchanges, becoming more and more acrimonious, and the drawing in of the British Minister, leading the Consul to comment to his Minister that Moore

“….has been more importunate and dissatisfied than any British Subject who has applied to me since I have had the honour of serving His Majesty.” [17]

It is interesting to note that while Moore was accompanied by Commander Moriarty R N and Major Humphrey Grey, both retired, in the early representations on behalf of the survivors, the last mentioned pair’s names did not appear on the correspondence in the later stages, and I speculate that they may not have been entirely on Moore’s side in his arguments with the Consul.

With the further help of the Royal Navy, on this occasion HMS ‘Thetis’, the final repairs and certificates were given on 21 February. The passengers commenced embarking on 28 February, but not without further approaches from Moore, and others originally destined for Van Dieman’s Land, demanding that the Captain be instructed, despite the terms of the contract, to transit Hobart en route to Port Jackson.

Consequently the remaining thirty one left Rio on the Brig “Anne” on 7 th March after five months in Rio. They were accompanied by a Scotsman looking to expand trade vie his family shipping service between Van Dieman’s land and India, as well as seven distressed Irish contract workers, stranded without employment in Rio.

Edward Conyngham’s Journey to New South Wales. 20 July 1828 to 8 July 1829. ‘Letitia’, ‘Hesperus’, and ‘Anne’.

Edward’s food allocation on the journey is known to us, as exact specifications were set out in the contract:

“Schedule of daily provisions [18] (3 women to be considered as equal to 2 men and 2 children to be considered as equal to one woman.)

One pound of bread; ¾ lb salt beef or salt pork; ¾ lb flour or ½ pint pease;

1 ½ oz sugar;1 oz coffee or cocoa;¼ oz tea;1 pint of wine;and Vinegar.

After a problem free journey from Rio, the ‘Anne’ arrived safely in Hobart on 3 June, 1829. In Kathleen Dougharty’s book, she stated that the ‘Anne’ stopped over in Capetown for a week, though I could find no published contemporary shipping records which make such a reference. Most passengers disembarked in Van Dieman’s Land.

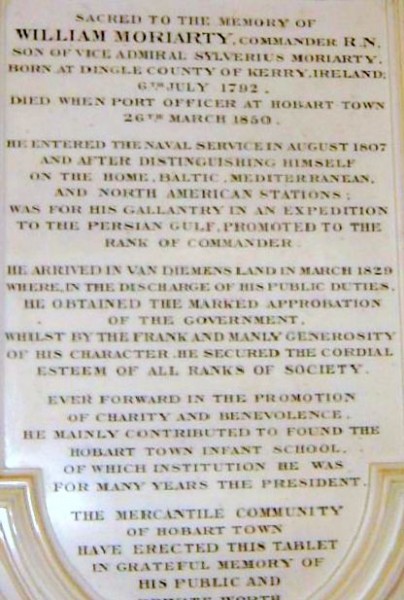

These passengers, living together for almost twelve months, now dispersed, many going on to be prominent members of Tasmanian society. The Greys went on to the land alongside Humphrey’s brothers in Avoca. Moriarty, with his family, took land near his sister Ellen Lucinda Moriarty in Deloraine, later becoming Port Officer in Georgetown, Magistrate in Westbury and finally Harbour Master in Hobart. The account of his funeral, including an obituary, is here. The Gee family joined John’s brothers in the Breadalbane/White Hills area. Joseph Henry Moore became a magistrate and civil servant. Frances Clerke, whose husband Alexander had returned to Ireland from Rio to recover other funds, is said to have taken up an appointment as a governess or teacher at Government House. When Alexander returned in 1830, they went to a 2000 acre land grant in Penguin, northern Tasmania, where he later became a involved in politics. There is some evidence that in later generations there was some intermarriage between the Moriarty and Clerke families.

The Hobart Colonial Times, reporting on their arrival, stated

“…the sufferers brought by this vessel who had been wrecked at St Jago on the 19th August last, per the Letitia, Captain Clements, from Ireland to New South Wales, and who having lost all their property, clothing and etc on board, are entitled to the highest commiseration:

We understand that Mr. Gray and family have already decided upon remaining in this colony and we doubt not the remainder of these emigrants, by a little kindness, would do the same particularly when they learn of the uncertain harvest in the sister colony, compared with bounteous plenty this colony enjoys from a gracious Providence, a salubrious climate, and a rich soil.”[19]

If his Excellency, however, should be restrained from doing so by any regulation from the Colonial Department, we at least trust he will forward their case to the Home government, with a recommendation to the above effect. We have no interest in the affair, further than the good of the Colony, to encourage emigration, and the common feeling of humanity we entertain for our fellow creatures, in which we are convinced no person can better participate in than Lieut. Governor Arthur.

We do not entertain a doubt but that a proper representation of the losses and sufferings of those emigrants, to the British Government, would be attended with success, and we feel persuaded that every one of them would obtain a grant of land in this colony at least equal to the property they shipped on board the Letitia, and also ample compensation for their sufferings, and loss of time, to which they are entitled by every consideration of humanity. We respectfully beg to suggest the opportunity that presents itself to the Lieutenant Governor, to give these careworn sufferers who ventured across the great deep to settle on our coasts, suitable grants of land to encourage them and in some measure to recompense them for their losses, free of all restrictions, that they be enabled to write home to their friends that their misfortunes have not been attended with utter ruin, or hopeless despair, and that they write home to encourage other emigrants to come here from the kind reception they meet. It is no excuse to charge them with neglecting insuring their property, when their own lives and those of their respective families were embarked in the same boat -with that property, but of which there was no insurance.”

Despite the ominous reference to the “uncertain harvest in the sister colony”, but doubtless endorsing the editor’s promotion of the principle of granting land and other support for the survivors, three of the weary group – Edward Conyngham, John McNamara and William Forster – continued on to Port Jackson on the ‘Anne’, leaving Hobart on 28 June after a three week stopover, arriving there on 8 July 1829.

Sydney at the time of Edward Conyngham’s arrival had a population of 15,000. Judge Roger Therry wrote of the period:

The streets were wide, well laid out, and clean. Two regiments-the 39th and 57th-the headquarters stationed in Sydney, were then on duty in the Colony. This considerable regimental force, with a large commissariat establishment, imparted quite a military aspect to the place. The houses were, for the most part, built in the English style, the shops well stocked, and the people one met in the streets presented the comfortable appearance of a prosperous community. The cages with parrots and cockatoos that hung from every shop door formed the first feature that reminded me that I was no longer in England. . . . Ground was not then so valuable there as it soon afterwards became, and commodious verandahed cottages, around which English roses clustered, with large gardens, were scattered through the town. There was scarcely a house without a flowerpot in front. A band of one of the regiments, around which a well-dressed group had gathered, was playing in the barrack- yard, and every object that presented itself favoured the impression that one had come amongst a gay and prosperous community. [20]

So our Edward Conyngham, 23, single, with no financial resources, having lost his assets in the shipwreck,[21] entered Sydney Harbour a week short of a year since leaving Cork. On disembarking in the Colony to start his new life, the Sydney immigration record[22] stated his ‘Profession, Trade or Calling’ to be “wireworker”. So far as we know, his only contact in the Colony was his brother Patrick, coach builder/wheelwright, who, though not yet free, was living in Sydney, where his first child was born and christened a month earlier.

_______________________

NOTE 1: Kate Hamilton Dougharty’s book “A Story of a Pioneer Family in Van Dieman’s Land” (published in Tasmania in 1953) has her story of the journey, including Humphrey Grey’s letter .

Appendix ONE: See her extract regarding the journey.

NOTE 2: Research Notes:

Appendix TWO: Contemporary Newspaper Reports.

AppendixTHREE: Ships of Interest.

Appendix FOUR: Cape Verde Islands, and Rio de Janeiro.

Appendix FIVE: British Consul’s Correspondence, Cape Verde Is.

Appendix SIX: British Consul’s Correspondence, Rio de Janeiro.

Appendix SEVEN: Funeral and Obituary of Captain William Moriarty.

- ‘In Search of Ireland’ H V Morton↵

- “Ireland” by Mr and Mrs S C Hall.↵

- This from Humphrey Grey’s actual letter, kindly provided by Dr Ian Broinowski of Hobart, a descendant of Grey. “A Story of a Pioneer Family in Van Dieman’s Land’ by Kate Hamilton Dougharty has abbreviated excerpts from the letter in her book.↵

- UK TNA Ref. F O 63/351↵

- Hawkesworth’s Voyages. Cook’s Third Voyage. 13 to 18 August 1772.↵

- ‘The Life of Captain Cook’ by J C Beaglehole. Chapter XIII.↵

- Consul Goodwin to The Treasury, London 2 October 1828. UK TNA Ref FO 63/339.↵

- Dublin Freeman’s Journal 19.12.1828; London Times 29.12.1828.↵

- Lord Ponsonby to A/CG Heatherley 16.11.1828.UK TNA Ref FO 13/50 p. 321.↵

- UK TNA Ref. F O 63/339.↵

- US Consul, Rio de Janeiro to US Secretary of State 17 June 1828. US National Archives microfilm T172 of Rio Consulate papers 1829/29.↵

- Some further research will be necessary in an effort to establish whether the “Hesperus” has any connection to the “Hesperus” in the Longfellow poem “The Wreck of the Hesperus”. There are many theories about the source of the Longfellow theme, including that there was no ship of this name wrecked in the 1839 storm off Boston, or that the ship was named “Herperus”, and other theories.↵

- Letter from passengers on the American Ship ‘Hesperus’ to Acting Consul General Heatherly , Rio de Juneiro October 6, 1828. UK TNA Ref FO 13/64.↵

- Historical Records of Australia 1829 p. 661.↵

- Consul Heatherly to Lord Ponsonby 15.11.1828.UK TNA Ref FO 13/50 P 317.↵

- UK TNA Ref FO 13/51 Page 311.↵

- UK TNA Ref FO 13/64 Page 76. 26.1.1829.↵

- UK TNA Ref. FO 13/51 Pages 313,314.↵

- Hobart Colonial Times 12.6.1829.↵

- ‘Reminiscences of Thirty Years in New South Wales’ by Roger Therry.↵

- He advised the Colonial Secretary on 18 February 1830 of “property £200 lost by me on the wreck of the Barque Letitia.”↵

- SRNSW ‘Landing Waiter and Port Surveyor, Port Jackson’ Report of Brig Anne arrival Port Jackson 8.7.1829.↵