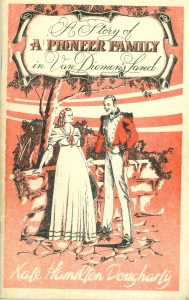

Extract covering the “Letitia/Hesperus/Anne” journey to Hobart,

from

“A Story of a Pioneer Family in Van Dieman’s Land”

by Kate Hamilton Dougharty – published in Hobart in 1953.

ooooooOOOOOOoooooo

Extract Begins:

The conclusion was that William and family would go ahead to Van Dieman’s Land……… and Humphrey, his family and three servants who wished to accompany them, would arrange with others wishing to emigrate, and would charter a sailing vessel and follow……………Meanwhile,……various friends wishing to travel with them, had combined to charter a vessel,and they had chosen one named “Letitia”. The Captain had good references and would engage a crew……………………….

……………

Mattie was a tower of strength. She and her son, Paddy Barnes,[1] would go to the end of the earth to be with the Greys, so they took it for granted that (they) would go to V.D.L. too. Mattie was given two cases, one for her personal belongings and the other for kitchen requirements. Some of her clothes got short shift when she stuffed in amongst them, a big iron kettle and some heavy iron saucepans.

…………….

Indeed, when she went on board, underneath her inherited green Donegal cape, her two favourite pots were tied securely round her waist. She had every intention of interviewing and routing the cook in his galley, making him clearly understand, that if she wished to cook there, she would brook no interference. She was, however, so smiling and confident, that he soon wondered if the galley were his or hers!

THE DEPARTURE

There was so much to think over. The girls wrote long lists for their mother – china, cutlery, glass, linen and a little of their old furniture. A big couch, some Chippendale chairs and the harpsichord on which they had already learnt their notes. Some books and rugs, a few home remedies for colds, beds, but not the beautiful four-poster which they hoped to get out later on, also wearing; apparel for all seasons (were there any shops in V.D.L.?).

They packed very few ornaments and only one or two pictures, and lastly, a painting by an artistic Grey of their home, Roscomroe. Everything must be ready a week before sailing. The two Humphreys packed the best available farm implements. They also bought clothes and hats suitable for the climate. Letters from V.D.L. made suggestions about what to bring, and hopefully, they packed good riding outfits.

The question of food was very pressing. In 1826, no fruits or vegetables could be preserved for long, so when those they had were used, then they must trust to getting more at various ports. Captain Cook’s early experience taught them to get cases of lemons or limes to prevent scurvy, liable to those who were obliged to live on salted butter and meat.

No tins of powdered or preserved milk had yet appeared, so Betsy, the little cow, had to travel with them, in the anxious care of Paddy Barnes. They hoped, if possible, to get a goat, for the Greys were not the only children on board, and milk was precious. There were a few crates of fowls and eggs, as a special treat. No one thought of preserving any. Lastly, a sow and piglets.

The last two or three days at Roscomroe were crowded. Neighbours came to bid them farewell, bringing gifts that they hoped would be useful. Young men, feeling the stir of adventure, called to note all the preparations. Many of them were Humphrey’s co-officers, eager to hear all they could. They sent messages or letters to friends in New South Wales or Van Diemen’s Land, with rather sketchy addresses. Ideas of geography were vague in those days and there was no post. A letter might be addressed –

Mrs. Prim,

New South Wales,

New Zealand and Van Diemen’s Land.

so it was just a matter of luck where it did land!

The Greys were asked to take delivery of a number of letters and guessing what a joy it must be to receive them, undertook to do their best, but is was understood that it might be a year or more before the right owner was found.

On board, Mrs. Grey tried not to sigh when she saw the cramped saloon, narrow cabins and hard berths, which were to comprise their home for many months. The two elder girls understood, and with Mattie’s help, tried to make things as comfortable as possible.

Henrietta and Lysbeth did not worry. Everything to them was exciting and it was only because of Biddy’s anxious care that they did not go head foremost down the hold. They were determined to miss nothing.

The sea was not very friendly for a few days, and no one was very happy. Then the gentlemen on board made a startling discovery. They knew very little about sailing, but apparently the crew, who had come aboard simply as means of getting to the colony, knew less, and in spite of his forcible language, the, Captain gave them little inducement to learn.

He seemed to know his job, and, fortunately as it turned out, the younger men took every chance to learn about the rigging and steering, and would climb up the masts daily, watching the coast- line and looking out for passing craft. The Captain had not been long at sea when he appeared to have a mighty thirst, and was often incapable, so the passengers had not only to put their new knowledge to the test, but also had to take over the management of the crew.

The voyage was a tremendous trial of endurance for the mothers. The food and accommodation question, and the anxiety about the health of their families, and their own health, no doctors were aboard, and the constant not-to-be-spoken-of worry as to what lay at the end of the journey, was always with them. Yet, there were days they enjoyed. The ship, looking beautiful, sailed on a calm .sea, with an even keel, and they sat on deck in the sunshine,

There were dreadful days too, when the little ship was only .a cockle-shell tossed on mountainous waves. All women and children were battened down below and not allowed on deck. Their men-kind, weary and worn, did not dare go to bed except for short intervals.

Then Mattie, a good sailor; rose to the occasion, She took supreme command of the galley, and was able to produce hot stews and boiling drinks at all hours. Like Mrs. Gummidge, so many men wanted to marry her, that she threatened to empty a bucket of dirty water over them if they persisted!

They must have been at sea a month when Humphrey wrote to his cousin.

Dear John,

I expect you will hear ere this reaches you of our shipwreck. We are, thank God, all safe, though with an entire loss of property, except for a few torn rags that we got on the shore, next day. On the 15th of August, we came to anchor in Porto Prayo Island of St. Jago, to take in water as what we had on board was very bad. It came on to blow, which occasioned a swell and the ship rolled much. It was deemed advisable to let go the second anchor, which was neglected by the Captain.

We were then in 8 fathoms of water with less than 30 :fathoms of chain, and about 3 o”clock on the evening of the 19th she parted from the anchor, the chain breaking. Then, too late, the second anchor was let go, but did not hold.

You can imagine what a situation we were in, leaving the boat and getting most of the passengers ashore. A signal was made, which brought a boat alongside. We instantly got all the .Ladies and Children in her and sent them ashore. Shortly after (at 4 o’clock), she struck on the rocks, in a dreadful surf.

She soon began to fill and her masts to roll which made it -dangerous to stay near her. I remained till her lower deck was forced up to the upper one. I am sorry to say that no exertion ‘was made to save the Ship or Cargo. The wind abated before the chain broke. I wanted Clements to let the kedge anchor be run from the ship, but he would take no notice of what any person said.

We can never give sufficient thanks to the Almighty, for, had it happened at night, I think we would not be saved.

From the great heat of the weather, the Ladies had on only a gown, no coat, and the gentlemen, jacket and trousers, and in that state, we are now obliged to remain, for want of others to change them. I have seen some shipwrecks, but anything to equal this, I have never witnessed. She was actually torn to pieces! We have experienced much kindness from Mr Goodwin, the British Consul, who provided us with provisions and lodgings during our stay, and a passage for as many as wished to go to Rio de Janeiro.

We left some of our passengers on the Island of St. Jago, who intended to return to Ireland by America, viz, Mr. Page, (son to Page, a stockbroker in Dublin) Mr. Hill, Dublin, Mr. Roberts, near Derry, and Doctor Clerk, of Skibbereen, Mrs. Weston and child (of Cork) who went on in the Mary of London the next day. She did not save a stitch of clothing nor a shilling of money. Mr. Murphy, of Dublin, also went in the Mary.

Now we have on board – Captain Allen, Master, bound to Rio, Mr. Moore of Dublin, his wife, four children and servant, Mr. Pentland, the Supercargo, Mr Onge, Dublin, Captain Moriarty, his wife, child and two friends of his – steerage passengers, Captain Clements’ wife and two children, Mr. L. W. Clerk (Skibbereen), and Mr. Popham from near Bandon. Also part of our former crew.

I must give you an account of our proceedings since we left Cork Harbour. We went to sea with the worst crew that ever was shipped on board any vessel. They could hardly work out of Cove. Repeatedly the Pilot said the crew knew nothing about the management of the ship. Mr Harris, the Customs House Officer, on taking leave of Captain Moriarty’s child, said, “My dear, I hope you may arrive in New South Wales, but I foresee it will not be in the Letitia!”

We had only five hands on board that knew anything about seamanship, and three of them were as great villains as could be met with. They were picked up in Cove, as the crew that shipped on board in Dublin left her in Cove. Repeatedly, these fellows said the ship would be lost for want of hands to work her. Clements said he would put into Madeira and ship three or four more hands. Instead of doing so, he went into the harbour, and finding the Port charges would be about £6, he stood out to sea putting us at the mercy of the waves, with a promise to put into Pernambuco for fresh water and provisions – Our water was bad four days after we left Cork as the casks that contained it were dirty and bad.

Almost every day there was a row between the Captain, passengers and crew. We were blessed with a fair wind from two -days after we sailed, until we anchored at Porta Prayo.

Your affectionate cousin, Humphrey

P.S. We arrived in Rio de Janeiro on Sunday, Oct. 5th., after a passage of 39 days from St. Jago, and came to lodge at Hotel de L’empire on Oct., 8th., 1826.

IN RIO DE JANEIRO

There they lived for about two years[2], in spite of many anxious enquiries in search of a suitable ship in which to continue their journey. At first it had been delightful to be on solid ground- have comfortable beds and good, though strangely prepared, food, but the terrible experiences they had been through, and the knowledge that they had not reached their journey’s end, made them long to leave. Also they had lost all their possessions, so carefully selected and packed, with which they had intended to furnish their new home.

Not one of the party could understand or speak Portuguese, and though there was a British Consul they could turn to, they longed to be with their own people. Fortunately, at the time of the wreck, Major Humphrey had been wearing a belt of sovereigns, which he had brought for contingencies, and he got these ashore safely, so there was enough for immediate necessities, and the Consul was very ready to help.

The children found everything exciting – they were too young to worry. With Martha and Biddy, they explored the very narrow streets of the town with its overhanging balconies, from which they could hear the voices and the lutes of lovers. They could not go out in the heat of the day. It was usually at dusk, just before their bedtime that they went, until Mrs. Grey realised that they were picking up the language and its meaning, much too quickly for her peace of mind, yet she could not keep them indoors all day.

The streets in Rio were curious in some respects, there was no mixture of different types of shops. The whole of one street might be shoe shops, the next all riding necessities and so on.

Mrs. Grey veiled herself and the girls like the Portuguese women, for Margaret’s golden-haired beauty and the freshness of their complexions had been attracting rather embarrassing attentions.

Soon after landing, the Governor of the district, who had heard of the shipwreck, sent to make kind enquiries and to invite the men of the party, with the Consul, to dinner at Government House. Everything was beautiful, but it was entirely a man’s dinner, neither a sign nor mention of ladies, so they took it for granted, the Governor was unmarried. He sent beautiful flowers and fruit to the Hotel for the ladies, and shortly afterwards called on them. He was a clever, good-looking man, with charming manners and liked to send his carriage and invite the whole family to take historical excursions with him, when he was out on circuit.

He was particularly charming to Margaret, so her parents were not altogether surprised when, at the end of a year, he asked her hand in marriage. She really liked him. They all did, but her father would not let her be pressed for an answer, She was after all, not quite 17, and the Governor twice her age.

Would she be happy with a foreigner and speaking a different language, though that trouble would soon be got over? But the life would be so strange to any she had known and she would have to change her religion to his.

“N0” her father decided. He thanked the Governor for the honour he wished to pay them, said he would tell Margaret but added that no pressure must be brought on her, He thought it might be six months or more before she would be expected to decide. She was very astonished when told. Though she knew that all girls married at seventeen or eighteen, she did not want to live far from her own people.

At last, a suitable ship was found and passages for all were taken on her, Mrs Grey had bought what china and furniture she could, to replace what had been lost, as nearly as possible. This, as well as a large quantity of tobacco, bought by the Major and his friends, had been sent on board, The cousins, though neither he nor they, cared for smoking, had written, saying it was much sought after in V.D.L. and as it grew profusely in Rio it might be a good speculation to bring some with them. The Greys had also been able to get a few fowls and another Betsy, though she was a reminder of the poor little one they had heard mooing at sea.

It was only a week before leaving. The Governor had gone off ‘on circuit’, but had written to say he would return two days before they left. He hoped that Margaret would think over and then accept his proposal. They need take no trouble about the wedding. He would see to everything. Her parents talked over things anxiously It Margaret married him, she would be certain of care and luxury, and the life in V.D.L. was so uncertain.

The day before they expected the Governor, the Greys all went for a country drive to a part they had not seen before. Practically all their luggage was on board so they had nothing to worry about. As they drove along they admired the very beautiful harbour and then noticed a fine white house in a lovely terraced garden.

The Major said to the driver of their coach “Whose house is that ?” and the man, smiling, replied, “That senhor, is the house for the Governor’s ladies.” The Major could not believe his ears. He looked, with horror, at Humphrey who was listening, then said “Do you mean His Excellency’s mother and sisters ?” “Oh no,” said the man, still smiling, “I mean the wives of Don Ameche.” “Perhaps the senhor does not know he has three ‘i”

The Senhor did not! He lost his breath for a moment, He let the drive go on as planned, then told the man they must return to the Hotel and on the way was quietly and quickly telling Humphrey what he had planned. He knew it would only lead to trouble to confront the villain and tell him exactly what he thought of him.

They must smuggle their dear, beautiful Margaret on board and keep her hidden until they had sailed. They would drive near the ship, the “Mary Ann,” then Humphrey, the girls and Biddy, would ask to be allowed to walk and go. to the: ship. This was not unusual as they had been there several times. The parents would say that they wished to go to the Hotel and rest, but Humphrey would accompany the girls to their cabin. He would promise to explain later to Margaret, then go off to consult the Captain, a fine trustworthy man. Should the captain have finished loading, he might, considering the circumstances and that the Greys were the largest party on board, arrange to get out to sea by an earlier tide. The Greys’ would notify the other passengers and they would all be safely away before Ameche returned to cause trouble.

The parents, Martha and Barnes, would take their usual evening walk but, this time, would go on board and as soon as possible, the captain would put off to sea. His father told Humphrey to lock the girls in their cabin and stay near it. He felt so furious, poor man and so insulted. Should he write and put in plain words what he thought of Ameche? No, the only thing to do was to run away.

Everything turned out as they had planned. Martha, with her son Barnes, quickly grasped the situation. She took his arm and in her cloak and mantilla, with a new pot under each arm, went on board. But she was determined, before she left to get even with the Don. She was not surprised to hear of ‘his villainy’! She had never liked him in spite of his good looks and charm. Never, never, would he have been good enough for her lovely Miss Margaret.

She knew of the costly gifts he had tried to bring Margaret, and that only flowers and fruit had been accepted. But several times lately, beautiful glass vases had accompanied the flowers, and it seemed paltry to return these, so Martha, taking a last look into Margaret’s room and telling no one, threw the flowers on the floor and trampled on them. Then, with her shoe, she smashed the vases and added the pieces to the flowers.

That was the only message left for, Don Ameche. He came, bearing exquisite flowers, and was told the birds had flown. He couldn’t believe it and insisted on seeing Margaret’s room, hoping for a note, but all he saw was Martha’s work, because, with the usual Portuguese “manana” (to-morrow) the room not being in use, had been left untouched. Humiliation indeed for a proud man, and by the time his first rage had expended itself on everyone near he had to realise that British subjects on a British ship, on the high seas were untouchable.

OFF AGAIN

Poor Mrs. Grey! In her wildest dreams, she could not have imagined that it was heaven to lie on a hard berth in a narrow ships cabin, but oh, the relief of knowing that once more they were amongst their own countrymen and that no unforseen danger threatened them!

Every morning, after breakfast they would have morning prayers and give thanks for the day’s safe journey, and in her thoughts she would add “I thank Thee, 0 God that Margaret is still with us.” She seemed as if she could not bear any of her family out of her sight, and the ship, being small made things easy for her

It could not be said that Margaret, in spite of the terror from which she had escaped, refrained from mischief and from causing havoc amongst eligible males. She had only to lift her long lashes and look at them admiringly when they climbed down from the rigging, up which they went daily, for them to land at her feet. Humphrey junior took her to task more than once, but after a short time gave it up. The minx could look so troubled and so innocent! Let them look after themselves!

Catherine was more reserved and shy, so was little eight year-old Henrietta, with her very big, deep blue eyes, her aquiline nose and long silky brown plaits. She was such a wise little woman, loving to mother her dolls, or anyone who was kind enough to have a headache! She had one great friend on board, John T. -, a young Scot[3], the son of a shipowner who was on his way to see what trade could be done between V.D.L. and India by their ships. He was so gentle and kind, even made a house for the dolls, and he had been about the world with his father.

Mrs. Grey was pleased when he came to show them the wonders of the sea, a school of porpoises playing happily near the ship, or flying fish, like fluorescent birds in the light of shining waves.

Lysbeth was the baby of the ship and her mother, Biddy and the girls were always on the watch, countering the effect of the lady’s getting too much attention. She was such a gay, happy, little person. On one occasion, Biddy, who had been in charge of her, missed her and was horrified to discover her climbing up the rigging to the applause of an irresponsible youth above her. Biddy was too frightened to call her, but quickly got a sailor who rescued her, then dragged the youth down and gave him such a trouncing that he dared not go near the masts for days.

Biddy took the pink-cheeked culprit to her mother, who decreed that Lysbeth must do nothing without telling the others, and the two elder girls would give her and Henrietta two hours tuition daily in reading, writing and sewing. Lysbeth did not shine in the last, but what can you expect from a five-year-old? Henrietta would contentedly sew long seams or make clothes for her dolls. Lysbeth learned quickly and by the end of the voyage, she could read as well as any of them and even recite short poems. She was .always devoted to Catherine, who taught her.

The rest of the voyage passed without any unusual incident. There were calm days or storm, the passengers taking everything philosophically in hope of the Utopia which they expected ahead. They spent a week in South Africa provisionin[4], and there went for drives, seeing all they could. One man, owner of a big property, met them at a friend’s home, and invited them all to his beautiful Dutch house. He was unmarried, and like Don Ameche, found Margaret’s beauty devastating, and begged her father to consider him as a son-in-law.

Made wary by the Rio experience, the Major refused to promise more than that the suitor (who had offered to make a settlement on her of £40,000 equal to £100,000 later) should hear from him from V.D.L. after Margaret’s wishes were ascertained. According to promise, he answered later “Margaret does not think she could live so far from us all, and we will not bring any pressure to bear on her. Her happiness is very deal’ to us all. Thank you, but our answer is No.” The suitor immediately replied that he would be quite ready to sell out and live in any colony she chose. But it was no use. Margaret had no wish to marry.

It was two years after leaving Ireland, before they arrived in V.D.L, and it was an intense relief to know they had, at last, reached the promised land[5]. They had an unpleasant crossing in Bass Strait, but once they entered the Tamar River the beauty of the coast line was most comforting.[6] Their’s was not the only ship to arrive. Some carried convicts but even these had an air of hope.

THE ARRIVAL

Captain James, waving frantically, gave them a delighted welcome. His bullocks and dray, filled with mattresses, cushions and rugs, waited patiently for them. Other family groups awaited the ship too. The sun was shining. Everything seemed propitious for a restful home coming.

James had engaged rooms at the Cornwall Hotel for the whole party, and there they were to stay, until their possessions could be brought ashore and essential china and furniture sent ahead, by -drays, to Avoca, to the William Greys, with whom they were to make a home until their own was built.

Major William had called his place Rockford, the name of his wife’s parents’ home in Ireland. When James built his, he called it Grey Fort.

Mrs. Grey and party had a much needed rest. After the cramped ship’s quarters, the hotel was palatial! Martha and Biddy took the girls for all available walks and though there were no shops, and most of the population lived in tents there was quite enough variety to amuse them. Their Mother, finding she might send a few letters to Ireland by the returning ship, was writing long criss-crossed ones, telling all the perils they had been through, of their safe arrival, and of James’ welcome. Sir Rowland Hill had ‘ll.ot yet brought in postal reforms, so letters travelled through the agency of friends. At that time, in England, sending one sheet, cost foul’ shillings for four hundred miles.

Then there were farewells to their fellow passengers with whom they had become friendly. They might not see one another again, for not all had their locations in adjoining districts, and unmade roads made transport difficult.

Land had then to be cleared, fences and houses built. They could keep in touch only with letters.

The Greys’ found family news awaiting them. The first was ‘from Ceylon from Humphrey’s youngest brother, Richard (Lieutenant 1st Ceylon Regiment). He wrote the usual long criss-cross letter :-

My dear Humphrey,

I need not describe my astonishment and satisfaction on receipt of a letter from Home, dated 12th of October, addressed to me’ by Sarah. It arrived on the 14th of March, and therein I find that you and :Mrs. Grey are settled in V.D.L., though I regret exceedingly,. from the tenor of her letter, to hear of the misfortunes that befell you and the remainder of the passengers of your ship, and that you sustained such a considerable loss, but thank God that your lives are spared, together with a thousand sovereigns which Sarah mentioned (no banks nor letters of Credit then in V.D.L.)

Had I known of your reaching V.D.L. an opportunity offered of sending you a letter by two officers, viz : Lieut. Fowkes A.D.C. to Sir Edward Barnes, and Lieut. de Lancy, A.D.C. to Sir Hudson Lowe, who expects to be Governor on Sir Edward’s departure. They are both particular friends of mine and their interest might have been of service to you. I understand that N.P. Wright, Judicial Commissioner here, a very worthy man, has a sister married to General’ Darling, Commandant of N.S.W. Should it be your opinion that a letter having this medium should be of any service to you, I can easily obtain it for you at any time.

By the Hobart Town papers which Fowkes and de Lancey have brought me, I regret to find that the aborigines have such a hostile attitude to the settlers. You may rest assured that a mild’ plan will never answer with individuals of their disposition. They must be given to fear us and there can be no possible way of bringing matters to a,’ close than by using severe means, which is to let them feel the superiority of our firearms to their spears and tomahawks. We have had substantial proof of the efficiency of this plan where we have as wild characters, in every sense of the ‘word, to deal with, as you have there. I mean the Vedas, armed with bows and arrows, spears and axes.

Mrs. Grey and I were reading through the distribution of the Company once elected to accompany Colonel Arthur in the pursuit of the Black River Gentlemen, and notice that your name does not appear as an individual in command of a party. I assure you we were most anxiously looking for it, but perhaps you were otherwise employed by the Colonel’s orders. I was rejoiced to find the name of an old friend mentioned as being in command-Darcy Wentworth of the 73rd, an old and sincere friend of mine, and of my brother French’s. We spent many days’ and nights’ hardship together, during the Randram’s Rebellion, and a more indefatigable officer I never had the opportunity of serving with. I hope you will call on him and make yourself known to him. I have not the smallest doubt that whatever service lies in his power he will be most happy to render to you and your family. Tell him I visited his old friend at Gonegadda and saw the Inmate, who resided there with him. He is well but the Fort is in a state of delapidation.

Should either duty or pleasure take you to Sydney, you may meet Captain Rossi, who, when I was in the Isle of Granu, was most kind and friendly to me. He was formerly of the first Ceylon. I understand he is the Chief Magistrate of Sydney. I regret I am not acquainted with any other person in your Colony.

It is time now my dear Humphrey, to render an account of myself, ……………….

Letters were serious matters in those days and not to be scrambled through. It was amusing and a little confusing the way Richard referred to his own and his brother’s wife as Mrs. Grey. He gained promotion in the army and stayed on in Ceylon, so he and his wife never did come “to pursue peace, happiness and prosperity in V.D.L.”

END of EXTRACT.

“Copyright for this extract had expired when published on this site”

- FCM Note: I cannot find their names, or of ‘Biddy, their young nurse’, referred to later, in the Hesperus passenger list or in any other documents or Hobart Port or Newspaper arrival details. Furthermore, despite her many references to Humphrey as “Major”, there is no evidence that he held such rank.↵

- FCM Note: In fact they were in Rio a little over five months – 5 October 1828 to 7 March 1829.↵

- FCM Note: .”The author later in the book records that Henrietta married the same “John” in Tasmania .Ancestry records marriage of Henrietta Emily Gray (sic) to John Thompson at Morwen, Tas on 29 April 1848. Henrietta would have been 27 on this date. Moreover, there does not appear to be a Thompson in the passenger list of the Hesperus , or among those who signed a letter to the British Acting Consul General in Rio in 1828. Nor among the arrival names in contemporary Hobart newspapers. In fact Thompson had arrived in Sydney on the ‘St George’ in 1843.↵

- FCM Note: I have been unsuccessful in my search for any record of the ship stopping in Capetown, though it may have stopped in another port.↵

- FCM Note: In fact, slightly under one year – 20 July 1828 – 3 June 1829. The Marine Dept Arrival Record MB2/39/1 Page 13 is incorrectly headed 1830.↵

- FCM Note: The ANNE did not call at Launceston, but only Hobart and, later, Port Jackson.↵